Abstract

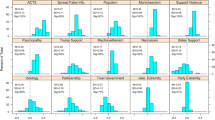

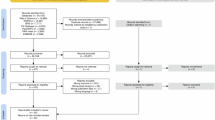

People differ in their general tendency to endorse conspiracy theories (that is, conspiracy mentality). Previous research yielded inconsistent findings on the relationship between conspiracy mentality and political orientation, showing a greater conspiracy mentality either among the political right (a linear relation) or amongst both the left and right extremes (a curvilinear relation). We revisited this relationship across two studies spanning 26 countries (combined N = 104,253) and found overall evidence for both linear and quadratic relations, albeit small and heterogeneous across countries. We also observed stronger support for conspiracy mentality among voters of opposition parties (that is, those deprived of political control). Nonetheless, the quadratic effect of political orientation remained significant when adjusting for political control deprivation. We conclude that conspiracy mentality is associated with extreme left- and especially extreme right-wing beliefs, and that this non-linear relation may be strengthened by, but is not reducible to, deprivation of political control.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data for study 1 and 2 are available at https://osf.io/jqnd6/.

Code availability

Custom code that supports the findings of this study is available as R markdown at https://osf.io/jqnd6/.

References

Swami, V. et al. Conspiracist ideation in Britain and Austria: evidence of a monological belief system and associations between individual psychological differences and real‐world and fictitious conspiracy theories. Br. J. Psychol. 102, 443–463 (2011).

Douglas, K. M. COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 24, 270–275 (2021).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. A bioweapon or a hoax? The link between distinct conspiracy beliefs about the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak and pandemic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 11, 1110–1118 (2020).

Golec de Zavala, A. & Federico, C. M. Collective narcissism and the growth of conspiracy thinking over the course of the 2016 United States presidential election: a longitudinal analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 1011–1018 (2018).

Douglas, K. M. et al. Understanding conspiracy theories. Adv. Political Psychol. 40, 3–35 (2019).

van Prooijen, J. W. The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories (Routledge, 2018).

Butter, M. & Knight, P. (eds) Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories (Routledge, 2020).

Sunstein, C. R. & Vermeule, A. Conspiracy theories: causes and cures. J. Political Philos. 17, 202–227 (2009).

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N. & Imhoff, R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: conspiracy mentality questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 4, 225 (2013).

Goertzel, T. Belief in conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 15, 731–742 (1994).

Wood, M. J., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Dead and alive: beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 3, 767–773 (2012).

Imhoff, R. & Bruder, M. Speaking (un-)truth to power: conspiracy mentality as a generalized political attitude. Eur. J. Personal. 28, 25–43 (2014).

Moscovici, S. in Changing Conceptions of Conspiracy (eds Graumann, C. F. & Moscovici, S.) 151–169 (Springer, 1987).

Moscovici, S. Reflections on the popularity of ‘conspiracy mentalities’. Int. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 33, 1–12 (2020).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. Too special to be duped: need for uniqueness motivates conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 47, 724–734 (2017).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. How paranoid are conspiracy believers? Towards a more fine-grained understanding of the connect and disconnect between paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 909–926 (2018).

Bergmann, E. Conspiracy and Populism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

Müller, J. W. Was ist Populismus?: Ein Essay (Suhrkamp Verlag, 2016).

Jolley, D. & Douglas, K. M. The social consequences of conspiracism: exposure to conspiracy theories decreases intentions to engage in politics and to reduce one’s carbon footprint. Br. J. Psychol. 105, 35–56 (2014).

Swami, V., Barron, D., Weis, L. & Furnham, A. To Brexit or not to Brexit: the roles of Islamophobia, conspiracist beliefs, and integrated threat in voting intentions for the United Kingdom European Union membership referendum. Br. J. Psychol. 109, 156–179 (2018).

Imhoff, R., Dieterle, L. & Lamberty, P. Resolving the puzzle of conspiracy worldview and political activism: belief in secret plots decreases normative but increases non-normative political engagement. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12, 71–79 (2021).

Jolley, D. & Paterson, J. L. Pylons ablaze: examining the role of 5G COVID‐19 conspiracy beliefs and support for violence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 59, 628–640 (2020).

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levinson, D. J. & Sanford, R. N. The Authoritarian Personality (Harper & Brothers, 1950).

Imhoff, R. in The Psychology of Conspiracy (eds Bilewicz, M., Cichocka, A. & Soral, W.) 122–141 (Routledge, 2015).

Abalakina‐Paap, M., Stephan, W. G., Craig, T. & Gregory, W. L. Beliefs in conspiracies. Political Psychol. 20, 637–647 (1999).

Đorđević, J. M., Žeželj, I. & Đurić, Ž. Beyond general political attitudes: conspiracy mentality as a global belief system predicts endorsement of international and local conspiracy theories. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 9, 144–158 (2021).

Grzesiak-Feldman, M. & Irzycka, M. Right-wing authoritarianism and conspiracy thinking in a Polish sample. Psychol. Rep. 105, 389–393 (2009).

Dieguez, S., Wagner-Egger, P. & Gauvrit, N. Nothing happens by accident, or does it? A low prior for randomness does not explain belief in conspiracy theories. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1762–1770 (2015).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M., Callan, M. J., Dawtry, R. J. & Harvey, A. J. Someone is pulling the strings: hypersensitive agency detection and belief in conspiracy theories. Think. Reason. 22, 57–77 (2016).

Gauchat, G. Politicization of science in the public sphere: a study of public trust in the United States, 1974 to 2010. Am. Sociol. Rev. 77, 167–187 (2012).

Jost, J. T., van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C. & Hardin, C. Ideological asymmetries in conformity, desire for shared reality, and the spread of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 23, 77–83 (2018).

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L. & Farhart, C. E. Conspiracy endorsement as motivated reasoning: the moderating roles of political knowledge and trust. Am. J. Political Sci. 60, 824–844 (2015).

van der Linden, S., Panagopoulos, C., Azevedo, F. & Jost, J. T. The paranoid style in American politics revisited: an ideological asymmetry in conspiratorial thinking. Political Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12681 (2020).

van Prooijen, J. W., Krouwel, A. P. & Pollet, T. V. Political extremism predicts belief in conspiracy theories. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6, 570–578 (2015).

Nera, K., Wagner-Egger, P., Bertin, P., Douglas, K. & Klein, O. A power-challenging theory of society, or a conservative mindset? Upward and downward conspiracy theories as ideologically distinct beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2769 (2021).

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y., Van Prooijen, J. W., Martinsson, J. & Markstedt, E. Does extreme political ideology predict conspiracy beliefs, economic evaluations and political trust? Evidence from Sweden. J. Soc. Political Psychol. 5, 435–462 (2017).

Babińska, M. & Bilewicz, M. in Uprzedzenia w Polsce 2017 [Prejudice in Poland 2017] (eds Stefaniak, A & Winiewski, M.) 307–327 (Liberi Libri, 2019).

Imhoff, R. & Decker, O. in Rechtsextremismus der Mitte (eds Decker O., Kiess J. & Brähler, E.) 130–145 (Psychosozial Verlag, 2013).

Arendt, H. The Origins of Totalitarianism Part 1: Antisemitism (Harcourt, Brace and World, 1951).

Brandt, M. J., Reyna, C., Chambers, J. R., Crawford, J. T. & Wetherell, G. The ideological-conflict hypothesis: intolerance among both liberals and conservatives. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 27–34 (2014).

Cichocka, A., Bilewicz, M., Jost, J. T., Marrouch, N. & Witkowska, M. On the grammar of politics—or why conservatives prefer nouns. Political Psychol. 37, 799–815 (2016).

Koch, A., Dorrough, A., Glöckner, A. & Imhoff, R. The ABC of society: perceived similarity in agency/socioeconomic success and conservative-progressive beliefs increases intergroup cooperation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 90, 103996 (2020).

Koch, A. et al. Groups’ warmth is a personal matter: understanding consensus on stereotype dimensions reconciles adversarial models of social evaluation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 89, 103995 (2020).

Sternisko, A., Cichocka, A. & van Bavel, J. The dark side of social movements: social identity, non-conformity, and the lure of conspiracy theories. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 35, 1–6 (2020).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Krouwel, A. P. Extreme political beliefs predict dogmatic intolerance. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 8, 292–300 (2017).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Krouwel, A. P. Psychological features of extreme political ideologies. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 28, 159–163 (2019).

Rooduijn, M. & Akkerman, T. Flank attacks: populism and left–right radicalism in Western Europe. Part. Politics 23, 193–204 (2017).

Oliver, J. E. & Wood, T. J. Conspiracy theories and the paranoid style(s) of mass opinion. Am. J. Political Sci. 58, 952–966 (2014).

Conway, L. G. III, Houck, S. C., Gornick, L. J. & Repke, M. A. Finding the Loch Ness monster: left‐wing authoritarianism in the United States. Political Psychol. 39, 1049–1067 (2018).

Van Hiel, A., Duriez, B. & Kossowska, M. The presence of left‐wing authoritarianism in Western Europe and its relationship with conservative ideology. Political Psychol. 27, 769–793 (2006).

Bartlett, J. & Miller, C. The Power of Unreason: Conspiracy Theories, Extremism and Counter-terrorism (Demos, 2010).

Douglas, K. M., Sutton, R. M. & Cichocka, A. The psychology of conspiracy theories. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 26, 538–542 (2017).

Sullivan, D., Landau, M. J. & Rothschild, Z. K. An existential function of enemyship: evidence that people attribute influence to personal and political enemies to compensate for threats to control. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 98, 434–449 (2010).

van Prooijen, J. W. & Acker, M. The influence of control on belief in conspiracy theories: conceptual and applied extensions. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 29, 753–761 (2015).

Stojanov, A. & Halberstadt, J. Does lack of control lead to conspiracy beliefs? A meta‐analysis. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 50, 955–968 (2020).

Kofta, M., Soral, W. & Bilewicz, M. What breeds conspiracy antisemitism? The role of political uncontrollability and uncertainty in the belief in Jewish conspiracy. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 118, 900–918 (2020).

Edelson, J., Alduncin, A., Krewson, C., Sieja, J. A. & Uscinski, J. E. The effect of conspiratorial thinking and motivated reasoning on belief in election fraud. Political Res. Q. 70, 933–946 (2017).

Uscinski, J. E. & Parent, J. M. American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford Univ. Press, 2014).

Nyhan, B. Media scandals are political events: how contextual factors affect public controversies over alleged misconduct by US governors. Political Res. Q. 70, 223–236 (2017).

Jost, J. T., Nosek, B. A. & Gosling, S. D. Ideology: its resurgence in social, personality, and political psychology. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3, 126–136 (2008).

Furnham, A. & Fenton-O’Creevy, M. Personality and political orientation. Personal. Individ. Diff. 129, 88–91 (2018).

Sibley, C. G., Osborne, D. & Duckitt, J. Personality and political orientation: meta-analysis and test of a threat-constraint model. J. Res. Personal. 46, 664–677 (2012).

Jost, J. T., Glaser, J., Kruglanski, A. W. & Sulloway, F. J. Political conservatism as motivated social cognition. Psychol. Bull. 129, 339–375 (2003).

Huber, J. D. Values and partisanship in left–right orientations: measuring ideology. Eur. J. Political Res. 17, 599–621 (1989).

Bauer, P. C., Barberá, P., Ackermann, K. & Venetz, A. Is the left–right scale a valid measure of ideology? Political Behav. 39, 553–583 (2017).

Malka, A., Soto, C. J., Inzlicht, M. & Lelkes, Y. Do needs for security and certainty predict cultural and economic conservatism? A cross-national analysis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 106, 1031–1051 (2014).

Bakker, R. et al. 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey. University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill www.chesdata.eu (2015).

Simonsohn, U. Two lines: a valid alternative to the invalid testing of U-shaped relationships with quadratic regressions. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 1, 538–555 (2018).

Jolley, D., Douglas, K. M. & Sutton, R. M. Blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel: the system‐justifying function of conspiracy theories. Political Psychol. 39, 465–478 (2018).

Leone, L., Giacomantonio, M. & Lauriola, M. Moral foundations, worldviews, moral absolutism and belief in conspiracy theories. Int. J. Psychol. 54, 197–204 (2019).

Marchlewska, M., Cichocka, A. & Kossowska, M. Addicted to answers: need for cognitive closure and the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 48, 109–117 (2018).

Cichocka, A., Marchlewska, M., Golec de Zavala, A. & Olechowski, M. “They will not control us”: in-group positivity and belief in intergroup conspiracies. Br. J. Psychol. 107, 556–576 (2016).

Imhoff, R. & Lamberty, P. in Routledge Handbook of Conspiracy Theories (eds Butter, M. & Knight, P.) 192–205 (Routledge, 2020).

Morisi, D., Jost, J. T. & Singh, V. An asymmetrical “President-in-power” effect. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 113, 614–620 (2019).

van Prooijen, J. ‐W. Why education predicts decreased belief in conspiracy theories. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 31, 50–58 (2017).

Bognar, E. in Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2018 (eds Newman, N. et al.) 84–85 (Reuters, 2018).

Összeesküvés-elméletek, álhírek, Babonák a Magyar közvelemenyben. Political Capital https://politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/pc-boll-konteo-20181107.pdf (2018).

Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). American Psychological Association http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx (2017).

Krouwel, A., Kutiyski, Y. & Thomeczek, P. EVES: European Voter Election Studies Survey Data (Kieskompas, 2019).

Rao, J. N. K., Yung, W. & Hidiroglou, M. A. Estimating equations for the analysis of survey data using poststratification information. Sankhyā: Indian J. Stat. A 364–378 (2002).

Valliant, R. Poststratification and conditional variance estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 88, 89–96 (1993).

Rutkowski, L. & Svetina, D. Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 74, 31–57 (2014).

Richter, D. & Schupp, J. The SOEP Innovation Sample (SOEP IS). Schmollers Jahrb. 135, 389–399 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work has been coordinated, presented and discussed within the framework of EU COST Action CA15101 ‘Comparative Analysis of Conspiracy Theories (COMPACT)’. German data stem from the 2014 Innovation Sample of the Socio-Economic Panel83 (SOEP). Data from the Andalusian survey conducted in Spain come from the research project ‘Conspiracy Theories and Disinformation’ directed by Estrella Gualda (University of Huelva, Spain), whose fieldwork was supported and executed by the Institute of Advanced Social Studies (IESA-CSIC) in the context of a grant received for executing the 5th Wave of the Citizen’s Panel Survey for Social Research in Andalusia (ref. EP-1707, PIE 201710E018, IESA/CSIC, https://panelpacis.net/; E.G.). The Czech part of the study was supported by grant 20-01214S (S.G.) from the Czech Science Foundation and by RVO: 68081740 (S.G.) of the Institute of Psychology, Czech Academy of Sciences. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.I. and J.-W.v.P. initiated the project with an open call. R.I., O.K., J.H.C.A., M.Bi., A.B., M.Ba., N.B., K.B., R.B., A.C., S.D., K.M.D., A.D., B.G., S.G., G.H., A.K., P.K., A.K., S.M., J.M.D., M.S.P., M.P., L.P., G.P., A.R., R.N.R., F.A.S., M.S., R.M.S., V.S., H.T., V.T., P.W.-E., I.Ž. and J.-W.v.P. contributed to the conception of study 1 and collected data in their respective country. A.K., Y.K. and T.E. provided the data for study 2. R.I. and F.Z. analysed and interpreted the data with helpful input from O.K. R.I. drafted the article. All authors provided critical revision and approved the final version of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Bruno Castanho Silva, Federico Vegetti and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information

Supplementary Sects. 1–12 and Tables S1–S25.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imhoff, R., Zimmer, F., Klein, O. et al. Conspiracy mentality and political orientation across 26 countries. Nat Hum Behav 6, 392–403 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01258-7